Saloua Raouda Choucair. Edited by Jessica Morgan. London: Tate Publishing, 2013.

One of the many myths of the Western canon is that European modern artists invented abstraction. Despite the known existence of pre-modern non-objective art among a number of non-Western cultures, twentieth-century European forays into pure abstraction are isolated as having developed radically new pictorial stances that changed worldviews across continents. That is not to say that what these artistic innovators formulated and realized was somehow minor; on the contrary, the political and socio-cultural possibilities of what they envisioned were profound, especially in the face of collapsing empires, between the two world wars, and in the wake of the United States’ post-war rise to power. For example, there is abstraction before and after Cubism, which tapped into the reimagining of space, time, and movement of the machine age; and there is certainly abstraction before and after Abstract Expressionism, which, in its early stages, used form to communicate the lingering nihilism of a world forever altered by nuclear warfare. At the moment, there is a multidisciplinary campaign to correct the shortcomings of this history of Modernism by looking past the borders of Euro-American art centers. It is within the experiments of artists who are noticeably absent from the Western view of art history, despite having been in pursuit of modern aesthetics, that examples of pre-modern abstraction are beginning to be reevaluated.

Currently on view at London’s Tate Modern is the first-ever museum exhibition to showcase the work of Saloua Raouda Choucair (b. 1916), a pioneering Lebanese modernist who sought to resume Islamic art’s investigation of infinity and its growth and movement of forms through the aesthetic aims of Modernism. The eponymous publication accompanying this retrospective provides a condensed overview of the artist’s oeuvre by contextualizing her work within local and international art movements and the milieu of Lebanon’s art scene. In addition to its ample serving of reproductions, the catalogue includes essays by the exhibition’s curators, Jessica Morgan and Ann Coxon, alongside the contributions of anthropologist and art historian Kirsten Scheid and art critic and essayist Kaelen Wilson-Goldie.

Jessica Morgan’s introduction to the monograph begins with the story of the artist’s 1949 visit to Marseille, France, where Le Corbusier’s post-war residential housing project “Cité radieuse” was under construction. The concrete structure was one of several buildings that were conceived as part of the architect’s Unité d`Habitation concept, which he developed with artist Nadir Afonso as a new prototype for communal living by integrating modular housing with the immediate amenities and designated spaces of a small town. Morgan describes Choucair’s fascination with the site as evidence of her interest in “a solution to a complex issue of space and form” and her frequent return to “the unit or model and its potential for duplication, interrelation, fabrication and extension.” Such preoccupations with space and the malleability of certain forms would lead the artist to work through various media, arriving at what Helen Khal identified as “pure form and architectonic force.” The examples Morgan invokes, Sculpture with a Thousand Pieces (1966-68), Infinite Structure (1963-65), and an untitled clay mockup for a coiled compound that could be extended by adding new compartments to its tail end, demonstrate Choucair’s analytical approach to art, namely how she linked the formal properties of geometric abstraction with the generative sequences of nature, in which individual units give life to new variations. The curator also notes the “experimental spirit” that drove her art and the high functionality underwriting her artistic designs, which she intended to apply beyond static art objects into the realm of urbanism.

Two aspects of the artist’s life are outlined in Morgan’s essay, which are then elaborated on by the publication’s subsequent texts: first, that Choucair was engaged in (and contributing to) international developments in art as they were unfolding; second, that she remained largely unknown in global art circles up until recently. A recurring argument of the included essays is that the artist never received the recognition she deserves because of the dismal social history of the Beirut art scene, which regularly succumbed to Lebanon’s political matrix.

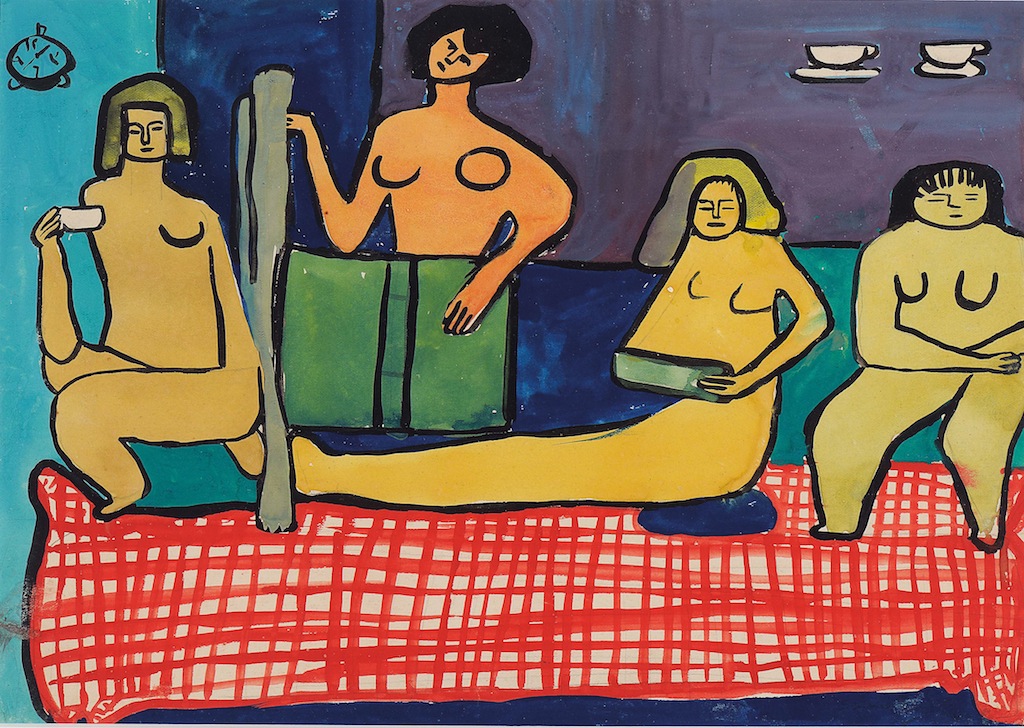

Kirsten Scheid’s essay, “Distinctions That Could be Drawn: Choucair’s Paris and Beirut,” delves into the artist’s time in Paris, where she attended the free atelier of French modernist painter Fernand Leger while studying at the École des Beaux-Arts between 1948 and 1952. Central to her interest in this period is how Choucair’s work was received, contextualized, and presented in both Paris and Beirut. Scheid’s entry is based on her doctorial dissertation Picture Makers and Lebanon: Ambiguous Identities in an Unsettled State (Princeton University, 2005), and includes a heavy dose of anthropological analysis. The few works of art that are discussed in detail reflect how Choucair was often working in direct contrast to (or at least deviating from) the labels, standards, and aesthetic strategies that were propagated by France’s waning post-war art scene, which were tweaked and exported to Beirut by various cultural agents. Scheid argues that much of the Lebanese art scene struggled to fully understand Choucair’s work and its theoretical approaches as she cites the numerous texts in which critics frequently caved in to the pressures of a cultural sphere that was tied to a nationalist project during the Cold War. Although her discussion of such framing is worthwhile, it is unfortunate that she does not take more frequent detours into the visuals of specific works. Her description of how Choucair subverted the male gaze of Le Grand Dejeuner (1921) by Leger in a series of gouache on paper works titled Les Peintres Celebres holds the reader’s attention with fascinating detail, as does her breakdown of the Lebanese artist’s mathematically based, abstract compositions. Reading Scheid’s essay, one senses she could have offered greater insight into the formal nature and historical significance of the exhibition’s selection of painting.

[Saloua Raouda Choucair, Les Peintres Celebres 1 (1948-9). Image copyright the

[Saloua Raouda Choucair, Les Peintres Celebres 1 (1948-9). Image copyright the

Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation. Courtesy of Tate Modern.]

In “The Potentiality of the Thing: Saloua Raouda Choucair’s modular sculpture” Ann Coxon examines the artist’s three-dimensional works by situating her artistic approaches between the pictorial directives of Islamic art and the “pursuit of abstraction” characterizing certain branches of mid-century Modernism. Coxon traces Choucair’s interest in non-objective art and design to 1943, when she traveled to Egypt and was immediately taken by its historic Islamic architecture. Several years later, once she resettled in Beirut following her time in Paris, she began to produce sculpture. In passing, Coxon notes that the artist’s initiation into sculpture in 1957 occurred after she returned to Lebanon from the United States, where she experimented with enamelwork and jewelry making. Although previous biographical records have placed Choucair at the Pratt Institute in New York and the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan during the mid 1950s, the Tate publication overlooks how her experiences in the United States might have directed her formative leap from painting to sculpture. A lack of engagement with this brief history is curious given that Cranbrook’s core curriculum, which dates back to the 1930s, is responsible for expanding the reach of American Modernism and has emphasized high levels of craftsmanship and functionality in architecture and design since the institute’s founding. By the time Choucair would have arrived at Cranbrook to train, the influence of the academy’s faculty and alumni, including its founding president, architect Eliel Saarinen, was felt across the United States in everything from sculpture to industrial design. In New York, in addition to the dynamism of an art scene that drew artists from across the globe, Choucair would have been surrounded by masterpieces of the International Style, which were constructed during the American post-war boom and were tailored to the vertical built environment of the city (the United Nations Headquarters is but one example). She also would have encountered Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum of Art, a structure that suggests self-sustained growth with the gradual momentum of its coiled skeleton. At the time, the modernist advocacy of merging form and function was also culminating in a mid century design renaissance that brought Isamu Noguchi, Frances Knoll, and Ray and Charles Eames (the latter three of which studied at Cranbrook) to the fore. Such information slightly alters the view of Choucair’s work in that it expands the range of Modernism in which she was participating; and, if investigated at greater length in the monograph, could have reinforced Morgan’s observation that the artist’s architectural projects and sculpture engage “mid century ideals of economy and efficacy.”

Despite this oversight, “The Potentiality of the Thing” offers the most in-depth artistic analysis of the publication’s included texts. Coxon provides a lengthy study of how the artist was intrigued by Islamic art’s use of simple forms, including the straight line and the curve, which can reach unparalleled heights of abstraction through repetition, symmetry, reorientation, and division. When working in France, Choucair identified the links between this precedent of geometric abstraction and the trials of European modernists who sought to abandon the figure. Coxon’s analysis of how “a system based on mathematics and unbound geometric units” was integral to the artist’s three-dimensional works covers several decades and examines numerous categories of sculpture (“closed forms,” “modules,” etc) with examples that were produced as late as the 1980s. Other reproductions from the 1990s confirm the author’s discussion of her interest in Arabic calligraphy and the structure of Arabic poetry, which led to the development of modular works that can be taken apart and rearranged or reassembled by the viewer.

[Saloua Raouda Choucair, Poem (1963-5). Image copyright the Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation. Courtesy of Tate Modern.]

[Saloua Raouda Choucair, Poem (1963-5). Image copyright the Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation. Courtesy of Tate Modern.]

Coxon’s explanation of the recurring themes of three-dimensional works also includes the observations of Lebanese colleagues who were early admirers of her attempts to expand the theoretical bases of Islamic art. The reverence with which Helen Khal and Samir Sayigh wrote about Choucair’s work, both as artists and critics, dislodges the publication’s belabored claim that she was unrecognized in her native country.

The publication’s final text, Kaelen Wilson-Goldie’s “Two Lovers in a Park at Midday: The urban imagination of Saloua Raouda Choucair,” clarifies this argument by emphasizing how a lack of cultural infrastructure and the absence of an operational art scene during the Lebanese civil war (a period that overshadowed the latter half of her career) led to a long list of unfinished or unrealized projects. Wilson-Goldie’s vivid detailing of the cityscape surrounding Bench (1998), one of two public sculptures by the artist, describes a contemporary context that was (and still is) unfit and far from ready for the groundbreaking, civic-minded conception of space that steered her practice. And yet, the author affirms, it is this exact setting that inspired Choucair.

Echoing Wilson-Goldie’s sentiments, it is surprising that Lebanon has produced so many outstanding artists given its relatively small size, political depravity, and ensnaring doctrine. It is also remarkable that the critical link between Islamic art and Modernism would emerge from an art scene that has convinced itself of its “cosmopolitan” nature with endless attempts to gain distance from regional markers, historic or otherwise. The only logical explanation for such incongruous developments is that conflict, struggle, and uncertainty often accelerate art’s necessity for reinvention.